Justice is our demand. No peace on stolen land.

For a hot second of last year, Palestine became a trend. It had a big wave of solidarity, a viral moment, its own fifteen minutes of fame with a spotlight that produced aesthetically pleasing but haphazardly researched Canva infographics before Instagram’s new era of activists moved on to the next popular cause – leaving little to none of the much needed sustainable change in their wake.

I guess dismantling apartheid regimes gets boring after a while?

I say this only half seriously. While I have a working list of grievances against social media activism culture (of which I am an active part), I can recognize what the propelment of the Palestinian cause into the palms of our hands gave to the movement. This influx of advocacy helped dismantle an idea of the “conflict” being too complex to advocate within, or too double sided to firmly sympathize with the Palestinian struggle. It publicly denounced the unreasonable notion of anti-Zionism being synonymous with antisemitism. It also woke much of the West up to ongoing issues of Islamophobia, policing, and settler colonialism – all dangerous affairs that exposed our own government’s active aiding and abetting in. Palestine needed this anti-imperialism spirit decades ago, so while I can’t be mad about it finally arriving, I can express my disappointment about it leaving our online social spheres just as quickly.

Free Palestine until it’s actually free, not until the media tells you to focus your attention elsewhere.

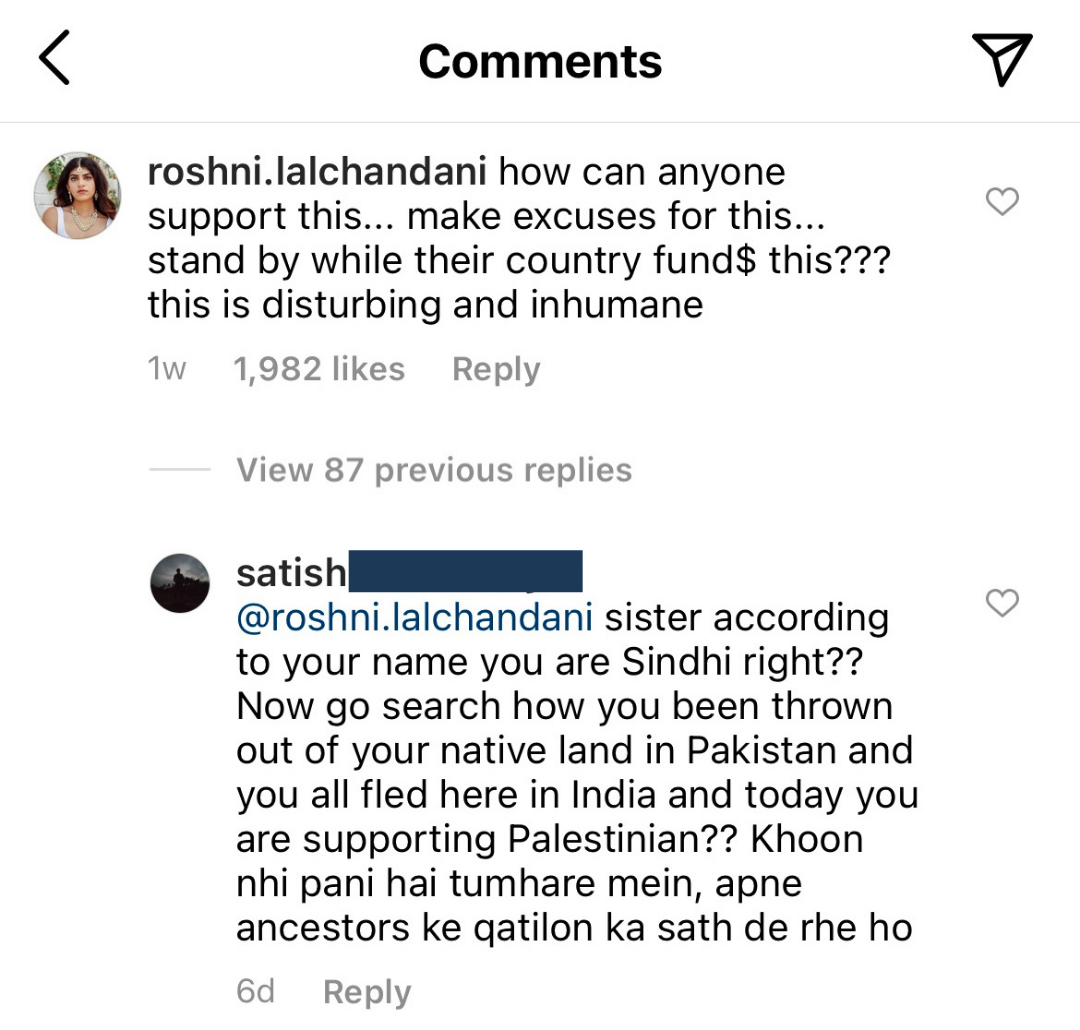

During that time, @theimeu shared a reel to their Instagram which showed a crowd of Israelis dancing and celebrating as the Al-Aqsa mosque burned behind them. This is during Ramadan, while residents of Sheikh Jarrah faced forced eviction, while Gaza and its children continued to be brutalized and bombed. It was jarring footage that openly revealed the callousness of the Israeli state. It shook me, and I felt compelled enough to leave a comment on the video.

Directly engaging with political accounts at all is rare for me as I can just barely tolerate the onslaught of malevolent responses my words inevitably provoke, and getting caught up in an online war with people whose inner empathy I cannot tap into from behind a screen is unproductive for me.

Satish and his assumption that my Sindhi identity would inherently position me against Palestine is a prime example. This argument is rooted in blatant Islamophobia and is unsurprising given his open support of the BJP (Modi and the Indian government ally themselves with Israel financially and politically, so it should shock no one that the rising Hindutva mobs of India blindly commend the oppressing state).

“Khoon nhi pani hai tumhare mein” or “You have water in you, not blood”

“apne ancestors ke qatilon ka sath de rhe ho” or “you’re murdering your ancestors alongside [Pakistanis]”

Weaponizing my Sindhi identity, which I have been sensitive about understanding for years, against me so to justify the decades worth of institutional violence against Palestinians is wildly offensive behavior. Satish doesn’t know me. He doesn’t know my grandparents or their parents. He hasn’t explored the history and identity of Sindhis enough to know that not only is his argument invalid in truth, but equally so in logic. It is the antithesis of reality.

My Sindhi identity enforces my Palestinian solidarity as the parallels between colonized and displaced ethnic groups throughout history remain consistent. That’s what this piece is about.

Loss of Culture

I’ve written about my internal struggles navigating the Sindhi identity at length before. Unlike the generation before me, who overcame their refugee struggle by overcompensating in patriotism for the new India, I long to return to my ancestral homeland, to sink my toes into the soil that bore my earliest family, which cultivated our culture rich in poetry and art, tastes and sounds. I imagine how lovely it would be to share a state where everyone spoke my first language, one that flows off the tongue with the same sweetness as the mangoes we’d pluck fresh from Sindh’s trees, slicing into squares for our children because there’s no easier way to say “I love you.”

Uprooted and scattered across the globe by way of our many migrants, the Sindhi language now grows more and more endangered with each passing generation. Though this threat of a culture’s eventual erasure isn’t unique to post-partition India; it’s a grim, often intentional, consequence for many colonized peoples. The Israeli government, for example, is deliberate in their eradication of Palestinian culture. From the burning of olive trees that generations of Palestinians had nourished, to the appropriation of Palestinian cuisine now repackaged as Israeli staples, to the outright refusal to honor the Palestinian right of return, Israel has left no stone unturned in their quest to create a warped sense of nationalism for themselves, one which relies on the destabilization of the Palestinian people and their pursuit of justice. For as long as a cohesive Palestinian identity inspires and unites an embodied resistance, the Israeli state will continue to disjoint that collective through every possible means.

Preceding Religious Tolerance

When I was a child, I remember carefully sliding the cassette tape of my parents’ wedding into the VCR, eager to see all my older relatives as their younger selves, celebrating in the cultural garb and high hairdos we laugh and cringe at now. When I watched my parents circumnavigate the Guru Granth Sahib during the Anand Karaj that sealed their love for life, I remember asking my mama – “If we’re Hindu then why do we also go to Gurdwara?”

“All of our neighbors in Sindh were Sikh or Muslim. When you spend so much time with people, when you come to love them, their beliefs intertwine with your own,” she said to me in Sindhi, making the sentiment all the more beautiful to my ears. It seemed so simple, so peaceful. If there is only one God then our differences aren’t so different, and definitely not so different that it should ever call for the bloodshed it did. “So why did it?” She explained religious persecution, riots and pogroms, with as much delicacy as you could to an 8 year old.

I give every ounce of my love to Waheguru, a devotion as permanent as the ink I’ve worn on my skin since I was nineteen. I wake up and whisper ek onkar, the tenet that guides every choice I make, every thought I allow to escape. My love reaches Allah too, calling out to the higher power in moments of anguish, discovering comfort in just the name and the essence. My spiritual practices grew from childhood Sundays spent at the mandir, bathing murtis in doodh, sewing malas out of Kroger clearance bouquets, sneaking bites of sheera before aarthi, the calming aroma of chandan scented agarpathis heavy in the air. The Sindhi identity is rooted in spiritual diversity, valuing the goodness in others above all else. Spewing divisive rhetoric that tore the people of the land apart from each other on grounds as sensitive as religion wasn’t just a hateful-turned-violent political move, but a devastating quake beneath the pillars Sindhis had defined themselves upon.

The majority of Sindhis worldwide are Muslim, just as the majority of Palestinians are. Despite belonging to the Hindu minority in Karachi, my grandparents tell pre-partition stories of living in harmony amongst their Muslim and Sikh peers. Similarly, before the advent of Zionism, there was a time where Muslims, Christians, and Jews cohabited peacefully within Palestine, sharing a history of tolerance and respect. While Palestinian Jews were granted Israeli citizenship, the Palestinian Christians and Muslims who remain in the region continue to suffer from occupation, apartheid, and ethnic cleansing. Meanwhile religious violence against Muslims by the Hindu majority in India has escalated exponentially, alongside violence against Hindu minorities by Muslim majorities in both Pakistan and Bangladesh. Sikhs continue to suffer on all sides.

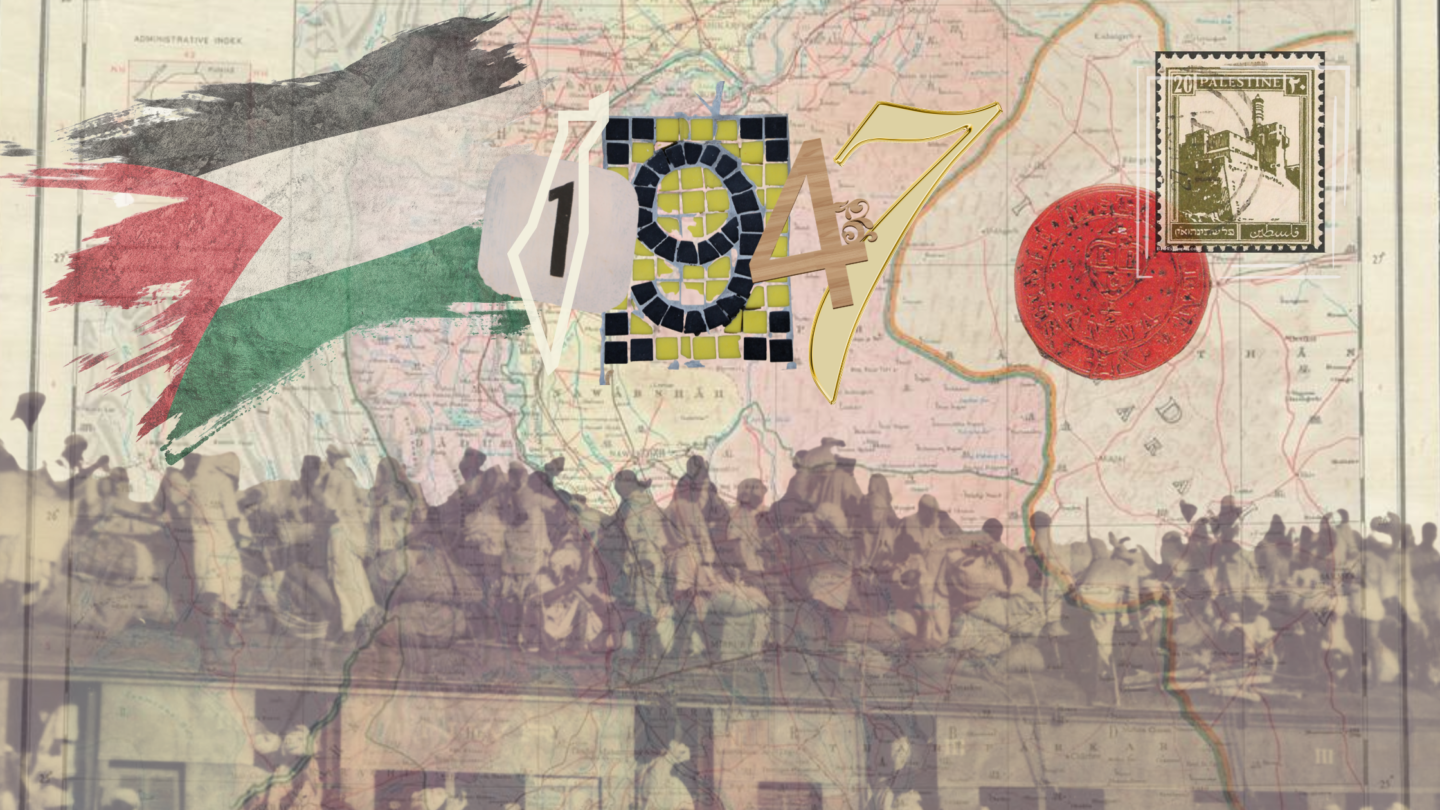

1947, From One Colonial Empire to Another

This hate is an ill-conceived case of misplaced blame. While the monarchy sips their (bland) tea and passively watches the decades-long religious and geopolitical war they ignited, one that they promoted for the sake of their own best interests, we satisfy them by refusing to hold them accountable for the flaws of our post-colonial state. Instead we point our fingers at each other – those who were once our own in the collective resistance against European tyranny – across the superficial, hastily drawn borders that now divide us.

1947. In one corner of the world, we saw a liberation, the end of a centuries long colonial despotism. In another, the nightmare had just begun. The same year that the British Raj left India, as we recovered from our own partition, the UN, encouraged by the British, drew up the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, which partitioned the country into separate Arab and Jewish states. Within months, this in turn triggered the nakba, or the 1948 Palestinian exodus, which permanently displaced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians and systematically destroyed upwards of 500 Palestinian villages, essentially putting an end to Palestinian society. People of color can’t catch a break, at least not as long as white supremacy continues to yield an iniquitous influence.

Just like India, the decision to partition Palestine was born out of what Europeans considered to be in their best interest. Zionism and the creation of Israel was not internationally advocated for out of support for Jewish people and their “right to self-determination” as many would believe, but rather because promoting Jewish statehood was an antisemitic means of expelling Jewish populations from Europe. Just a decade before Arthur Balfour, the foreign secretary in 1917, declared that Britain ““view[s] with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people,” he had vehemently supported the 1905 Aliens Act, which severely restricted Jewish immigration into the United Kingdom. Other European countries of wealth followed this lead, even training Zionist fighters in an effort to promote their own nation’s Jewish emigration.

Fascism in all its forms, by any which people, should be unequivocally condemned. From the British crown’s subjugation of India, to modern India’s own growing Hindutva ideologies, to the international war crimes being conducted daily by the Israeli state on the open-air prisons that is the remainder of Palestine, will we ever see a moment in history that is wholly shielded from oppression?

I didn’t exist in the time of India’s partition, but every day I reap the benefits of my ancestor’s bravery, bask in the privileges their sorrows afforded me. Their sacrifices are never in vain, never taken for granted. I can honor them and their stories, pay homage to my own heritage, by standing in deep solidarity with Palestinians. I can adopt their struggles as if they were mine, because two generations ago they were. Though I cannot walk the grounds of Sindh today, I can march through the streets of New York, Los Angeles, DC, or any other of the organized, collective efforts that are helping establish liberation for a people not so unlike my own.

Resistance continues until liberation.

We say from the river to the sea, Palestine will be free. I also say Palestine zindabad. When you’re born into a community of historically traumatized peoples, revolution doesn’t scare you as much. It becomes less daunting and formidable, more wishful and inspired. Our impulse to organize manifests into a hereditary trait, passed down through lineages until the vision for a liberated future is finally designed. How will we get there? Until my dying breath, I intend to find out.

Yours in solidarity,

Rosh

(Note: Violence against Islam’s third most holy site during Ramadan wasn’t new or unique to the events of last year. It’s happening right now as I publish and as you read. See my links page to find ways you can support occupied Palestine.)